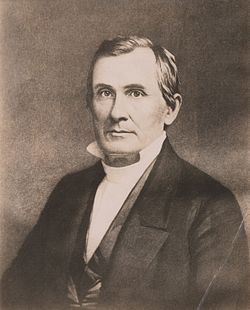

the Reverend Doctor George Washington Junkin, and what he means both for Gettysburg as we commemorate the 150th anniversary of that battle and for the Mainline.

Junkin had an interesting life. A native of Pennsylvania, he was an Old School Presbyterian minister turned president of three colleges/universities (Lafayette College, Miami of Ohio, and Washington College -- now Washington and Lee University), he watched as his school turned against both him personally and the nation he believed that God had divinely crafted in the form of the United States. He and some of his family left Virginia shortly before the Civil War began, though not all of them. Several relatives (including most famously his son-in-law, Thomas Jackson, and his daughter, Margaret Junkin Preston -- who became known as the poetress of the Confederacy) rejected the Union he so loved, and threw their lot in with the Confederacy.

In the book I am currently working on, Junkin looms large, as much of it takes place in Lexington, Virginia at both Washington College and at the nearby Virginia Military Institute, where the Davidson family had strong ties. In Junkin we get a glimpse of so much of the Mainline of the mid-nineteenth century, one that was dominated by the evangelical Protestant denominations of the Second Great Awakening (the Methodists, the Baptists, and the Presbyterians). But we also get a glimpse at how fragmented that evangelicalism was. All three of those denominations, the largest churches in the United States, split over the issue of slavery in the years before the Civil War. In the case of the Presbyterians, they had already broken into two camps over other issues (though slavery played an increasing role), but had managed to largely stick together somewhat officially until nearly the very end.

When it came to slavery, Junkin and the Old School walked a very fine line. Junkin himself owned slaves (after he moved to Virginia to take the Washington College job), had attacked abolitionists (while living in Ohio), but also supported the American Colonization Society. Indeed, he probably got the job in Lexington, in part because the previous college president had become to vocal on his belief that slavery had led to economic stagnation in Virginia. His branch of the Presbyterian denomination found no Biblical reason to believe slavery to be a sin, though most Northern Old Schoolers did believe it (like virtually any human institution) could lead to sin. By the time of the Civil War, however the Southern component of the Old School was less and less likely to agree with their Northern counterparts, and indeed, would form their own denomination as war clouds began to gather.

What does this have to do with the Mainline of today? Well, several things actually. First, is that theological and doctrinal complexity (and sometimes gymnastics) are nothing new within the Mainline. While we might talk of the "evangelical denominations" (and I surely do), there were very real difference between and among the Methodists, Baptists, and Presbyterians of Junkin's time. They did not always agree with each other, internally or externally, and it would be surprising if the modern Mainline did as well. Likewise, those differences mattered, and in someways drove membership and engagement that makes modern "consensus" efforts look meager in comparison. They may not have always been right, but they also weren't always wrong on matters of faith either. Second, is that these denominations were fully engaged with both their nation and their national culture. They were active in trying to shape it (whether in condemning slavery as a sin, working to keep the nation together, or -- even-- in trying to form a new nation in the Confederacy), much more than they were being shaped by it. And they were calling their members to political action (in ways that would probably make modern Church/State separationists's heads spin). Recent scholarship (such as the this) that in essence blames the rise of evangelicals and their engagement in politics on the slavery issue as the chief cause of the Civil War -- or else the inability for politicians to craft a compromise short of war misses the point that denominations were already engaged on both sides of the issue (and that evangelicals in England had helped end slavery there without a war). Junkin's story also reminds us of one other thing, using political labels like "liberal" and "conservative" can be problematic. Some recent scholarship (see here for an example) has argued that liberal Protestantism of the mid-nineteenth century gave birth to the liberal Protestantism of the early twentieth (and hence, to that of the twenty-first century as well), in large part because they had to reject Biblical literalism in order to condemn slavery. But Northern Old School Presbyterians never doubted that slavery could lead to sin, even if it was mentioned in the Bible. What they wrestled with was how to deal with the institution. In short, there is much more complexity to their time, and to ours, than labels often have us believe. And Junkin proved, as much as he was a man of his time, to be able to be "liberal" on some things, and "conservative" on others. Indeed, it was his conservatism that made him into a Unionist--to the point that he shook the very soil of Virginia off his shoes and wiped it from his wagon wheels when he left the state.

As for Junkin and Gettysburg, after leaving Lexington in the spring of 1861, Junkin returned to Pennsylvania. After the battle was over in 1863, the aged reverend made his way to Gettysburg, where he began ministering to the wounded and amongst the captured Confederates as well. Among the prisoners, he discovered several former students, whom he astounded by pulling from one of his pockets a class list and talking about their course work and grades. Surely this was a surreal moment. Surely as well it was a reminder of what they (and the nation) had once been, and would one day be again.

No comments:

Post a Comment