This week, in addition to enjoying summer break (personally, with my family as well as professionally, by getting some work done) I have been doing some various blog/article reading on what some might consider to be the Great Divide in American Protestant Religious History of the twentieth century: that between the Religious Left and Religious Right.

Now, this topic is one that I talk a good deal about in The Mainline, so I won't go over what I say there here. Rather, I want to say a few things about what I've been reading as well as touch on something else that this great divide has gotten me thinking about while I soak up the summer sun. First, there are the articles announcing the decline of the Religious Right/resurgence of the Religious Left (which is something I mentioned in the book might happen, and more likely would be something that scholars claimed following the election of President Obama in 2008). There is little doubt that there has been an out pouring of scholarship of late on the Religious Left/Liberal evangelicals (here is a New York Times article about it), and that this is important in its own right, as well as something (from an academic stand point) to be welcomed. Liberal Protestantism does need more study, and doing so might also add more nuance to the discussion of Mainline decline as well as better appreciate the complexities of American Protestantism and how it has related to American culture and politics in the last 50 to 60 years.

That being said, should it be triumphant? Some of this scholarship seems to imply that liberal Protestantism is responsible for the civil rights movement, the Great Society, indeed of "liberalism" in the American political and cultural senses. And at least some recent polls seem to argue that Religious Progressives/Religious Left are growing in the United States and that decline has (at last, some of them say) set into the Religious Right.

It sounds nice, but it falls flat I think. As some of these scholars point out, what they really need to study (and is also perhaps a large flaw in the above argument) is why liberalism continued in American life/culture, but liberal Protestantism did not. But there are other problems with this hypothesis as well, chiefly that it discounts Roman Catholics and their contributions to these projects, it assumes that denominational pronouncements reflect congregational realities, and assumes that religious conservatives did not have a hand in shaping some of these trends as well (not just in terms of opposition, but also in offering different courses to travel the same journey). And as for the triumphant talk based on polls, I will allow others who have read the data do the dissection, here and here. Needless to say, I am not ready to pronounce either the Religious Left triumphant, nor declare the Religious Right dead. Indeed, one of the other articles I have read this week reminded me (and other readers) that the Religious Right has a much longer history than it is sometimes given credit for (and as such, not only is there more study to be done on it, but it probably is stronger than a it is currently being credited for). That complexity, I hope, is something else I touched on in the pages of The Mainline.

So, if none of these articles, as good and as informative as they were -- and whether I agreed with them entirely or not -- was not the sum of my ruminations, then what was? Well, dear reader, like any good inquiry, such reading got me thinking. And what I got to thinking about was whether or not this Great Divide (Left and Right) was worth more ink (at least from me, at least right now), or if there was something else -- right under the surface of these articles/arguments, that demands more attention. If I had limitless time, I might just be pondering if we needed to study a great divide that was greater still than Left and Right in American Religious History, one that as I have thought about it deserves much more attention than either just in passing within larger works or that is largely ignored by focusing on groups/denominational leadership. And that Great Divide is the one between rural, suburban, and urban congregations in the progress of American Religious History, past, present, and future.

Perhaps it is because my son (the younger of my children) asked this week if we lived in a rural place or in the city and my daughter, the older, more experienced one in the ways of the world and social study terminology, was quick to offer (correct) textbook answers. Maybe it was because I read a really great article about American Religious History and Indiana (kudos Elesha Coffman). Perhaps it is because I grew up in a rural community, moved to an urban one, and now reside in a rapidly suburban one. Or maybe it is just because I think increasingly that place matters. Where you are shapes who you are (in both good ways and bad), and shapes what you do while you are there (as my First Year Seminar students learn when I subject them to a professor led campus tour each Fall). The long and the short of it is that I think we might understand the rise/fall/rise (and dare I even argue formulation) of both the Religious Left and the Religious Right better IF we started looking at how rural, suburban, urban impacted the congregations that made up the denominations that came to make up both. It would lead to some interesting questions, like did/do rural Catholics and rural Protestants share the same values/beliefs more so than there urban co-denominationalists? Where are we more apt to find non-denominationalism (and why)? Does having a denominational headquarters (and its location) matter to how representative its pronouncements on issues are?

Those are some of the questions that came to mind as I have dwelt on the topic this week. I think that studying this Great Divide could prove interesting. It might even be more important, in the long run, to understanding what has driven the Mainline of the Seven Sisters, as well as the new one I believe has emerged within American Christianity.

This blog is my "first draft" at writing, it is where I comment on my works and books(Prohibition is Here to Stay, 2009; Mainline Christianity, 2012; Interpreting the Prohibition Era,2014; Dis-History,2017, Rebel Bulldog, 2017) as well as current events. All views are personal, not meant to imply official sanction by any institution, and all posts are copyrighted to the fullest extent they can be. Enjoy!

Friday, July 26, 2013

Sunday, July 7, 2013

Signs (on I-65)

My family and I just finished a trip (whether it was a "jaunt" in the words of my wife because we were traveling North/South; or "cross-country" which I argued for since we covered parts of five states, even if it wasn't East/West) that took us along Interstate 65.

The past few years have seen us travel more by air than by car, and while this journey was not without its challenges, it was also a nice change of pace, and one that gave time for reflection.

The past few years have seen us travel more by air than by car, and while this journey was not without its challenges, it was also a nice change of pace, and one that gave time for reflection.

Within a mile or two along I-65 in Alabama, we encountered three signs that got me thinking a bit about American Christianity, not just because that is what I study and the Mainline was all about, but also because we were traveling during the July 4th/Independence Day holiday weekend. The first sign was a patriotic one, proclaiming "America: Love it or Leave it!"

Just down the road, on the same property was this one (which I actually found a picture of online, so my thanks to whomever took it):

Considering that we were in the midst of the Bible Belt, and if one small town we drove through once we got off of I-65 was any indication a very (Southern) Baptist portion of said belt (I counted four different Baptist congregations as we drove through maybe a 6 or 7 block stretch of this little community), I was hardly surprised (theological soundness being open to debate) to see such a religious message either -- though I'm not sure I've ever seen the "red devil" with the Grim Reaper scythe before, but it certainly fits the message.

Considering that we were in the midst of the Bible Belt, and if one small town we drove through once we got off of I-65 was any indication a very (Southern) Baptist portion of said belt (I counted four different Baptist congregations as we drove through maybe a 6 or 7 block stretch of this little community), I was hardly surprised (theological soundness being open to debate) to see such a religious message either -- though I'm not sure I've ever seen the "red devil" with the Grim Reaper scythe before, but it certainly fits the message.

Now, those two signs alone were enough to get me thinking. After all, there has been some discussion of late as to what degree American Christians (with special focus on evangelical Protestants) can/are/should/should not be patriotic towards the United States (see here and here for examples). Having grown up in an area of the country where there are churches with strong pacifistic beliefs, such debates are nothing new to me. But some of the discussion is not of "blind patriotism" but rather over if it is even right for a Christian to be patriotic at all. Some evangelical Protestants have, it seems, soured on politics (or now believe that the federal government is an agent of secularism) -- where a few years ago they were embracing politics and approving various aspects of U.S. foreign policy. But before we see this only in terms of the Religious Right, I'd caution us to also remember that some denominations that today are heralding the federal government today, a few years ago were actively opposed to White House. While I'd like to see more research done on this, at first glance, it would seem that what we have here is not so much a serious theological or doctrinal debate, but rather the degree to which politics is reflected via denomination pronouncements. Of course, anyone reading The Mainline will also soon come to understand my take that those pronouncements don't always fit well with everyone in the pews -- one way or another.

But that wasn't the end of the "signs on I-65"! Just down the interstate from these two signs is another one, letting visitors know about the Confederate Memorial Park. The park was the former home of the Alabama Confederate Home, and contains a museum, research facility, and cemeteries on the home's grounds. Having just celebrated the 4th of July and America's Declaration of Independence (not to mention having just passed the aforementioned "sign number one"), the sign for the Confederate Park was somewhat of a jarring reminder of the Civil War. A war that was foreshadowed by the division of America's great evangelical Protestant (Baptist, Methodist, Presbyterian) denominations over the issue of slavery, and which saw American Christians in both armies killing one another. All the while, assured that God was on their side. Perhaps nowhere was this summed up better than in President Abraham Lincoln's Second Inaugural, when he noted that "Both read the same Bible and pray to the same God, and each invokes His aid against the other." While there have been some good (and not so good) books written on faith during the Civil War, I think this area is still open for more good and fruitful research.

In the end, Christians -- by virtue of their faith -- are citizens of God's Kingdom. And with that citizenship, comes certain rights and responsibilities. But wherever they are physically located, they are also citizens of a particular nation. While Christianity is a global or international faith (whichever you prefer), indeed it is maybe the best example of a trans-national institution/organization, it is also a very local faith. The churches that sprang up in the New Testament writings were in particular places (reflecting those particular areas), but they were also all part of a larger political structure: The Roman Empire. The New Testament era of the Church's history was bound together not just by its common faith, but also by it being a part of the Roman World (and all that came with it, both in the good/bad and short/long term). How the Church has interacted with the State (as I've argued before) is a huge field of study -- and not just for the history of American Christianity. But we must also remember that citizenship in the State also comes with its own set of rights and responsibilities. In the end, Christians are bound by the words of Christ in Mark 12:17 when it comes to the dual nature of an individual's citizenship. Sometimes, perhaps, Christians will be called upon to support their nation, and other times they will be called upon to call upon their nation's leaders to change course. Both can be expressions of patriotism, but neither form of patriotism should be a substitute for faith itself.

Within a mile or two along I-65 in Alabama, we encountered three signs that got me thinking a bit about American Christianity, not just because that is what I study and the Mainline was all about, but also because we were traveling during the July 4th/Independence Day holiday weekend. The first sign was a patriotic one, proclaiming "America: Love it or Leave it!"

Just down the road, on the same property was this one (which I actually found a picture of online, so my thanks to whomever took it):

Now, those two signs alone were enough to get me thinking. After all, there has been some discussion of late as to what degree American Christians (with special focus on evangelical Protestants) can/are/should/should not be patriotic towards the United States (see here and here for examples). Having grown up in an area of the country where there are churches with strong pacifistic beliefs, such debates are nothing new to me. But some of the discussion is not of "blind patriotism" but rather over if it is even right for a Christian to be patriotic at all. Some evangelical Protestants have, it seems, soured on politics (or now believe that the federal government is an agent of secularism) -- where a few years ago they were embracing politics and approving various aspects of U.S. foreign policy. But before we see this only in terms of the Religious Right, I'd caution us to also remember that some denominations that today are heralding the federal government today, a few years ago were actively opposed to White House. While I'd like to see more research done on this, at first glance, it would seem that what we have here is not so much a serious theological or doctrinal debate, but rather the degree to which politics is reflected via denomination pronouncements. Of course, anyone reading The Mainline will also soon come to understand my take that those pronouncements don't always fit well with everyone in the pews -- one way or another.

But that wasn't the end of the "signs on I-65"! Just down the interstate from these two signs is another one, letting visitors know about the Confederate Memorial Park. The park was the former home of the Alabama Confederate Home, and contains a museum, research facility, and cemeteries on the home's grounds. Having just celebrated the 4th of July and America's Declaration of Independence (not to mention having just passed the aforementioned "sign number one"), the sign for the Confederate Park was somewhat of a jarring reminder of the Civil War. A war that was foreshadowed by the division of America's great evangelical Protestant (Baptist, Methodist, Presbyterian) denominations over the issue of slavery, and which saw American Christians in both armies killing one another. All the while, assured that God was on their side. Perhaps nowhere was this summed up better than in President Abraham Lincoln's Second Inaugural, when he noted that "Both read the same Bible and pray to the same God, and each invokes His aid against the other." While there have been some good (and not so good) books written on faith during the Civil War, I think this area is still open for more good and fruitful research.

In the end, Christians -- by virtue of their faith -- are citizens of God's Kingdom. And with that citizenship, comes certain rights and responsibilities. But wherever they are physically located, they are also citizens of a particular nation. While Christianity is a global or international faith (whichever you prefer), indeed it is maybe the best example of a trans-national institution/organization, it is also a very local faith. The churches that sprang up in the New Testament writings were in particular places (reflecting those particular areas), but they were also all part of a larger political structure: The Roman Empire. The New Testament era of the Church's history was bound together not just by its common faith, but also by it being a part of the Roman World (and all that came with it, both in the good/bad and short/long term). How the Church has interacted with the State (as I've argued before) is a huge field of study -- and not just for the history of American Christianity. But we must also remember that citizenship in the State also comes with its own set of rights and responsibilities. In the end, Christians are bound by the words of Christ in Mark 12:17 when it comes to the dual nature of an individual's citizenship. Sometimes, perhaps, Christians will be called upon to support their nation, and other times they will be called upon to call upon their nation's leaders to change course. Both can be expressions of patriotism, but neither form of patriotism should be a substitute for faith itself.

Tuesday, July 2, 2013

Old School

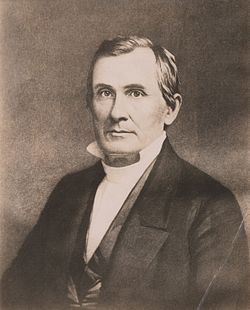

I am not actually sure when I first had to memorize Lincoln's Gettysburg Address. But I do know that the older I get, the more I study, and the more I write, the more I appreciate it. That being said, this isn't really a post about either Lincoln or the Address per se. Rather it is more about this guy:

the Reverend Doctor George Washington Junkin, and what he means both for Gettysburg as we commemorate the 150th anniversary of that battle and for the Mainline.

the Reverend Doctor George Washington Junkin, and what he means both for Gettysburg as we commemorate the 150th anniversary of that battle and for the Mainline.

Junkin had an interesting life. A native of Pennsylvania, he was an Old School Presbyterian minister turned president of three colleges/universities (Lafayette College, Miami of Ohio, and Washington College -- now Washington and Lee University), he watched as his school turned against both him personally and the nation he believed that God had divinely crafted in the form of the United States. He and some of his family left Virginia shortly before the Civil War began, though not all of them. Several relatives (including most famously his son-in-law, Thomas Jackson, and his daughter, Margaret Junkin Preston -- who became known as the poetress of the Confederacy) rejected the Union he so loved, and threw their lot in with the Confederacy.

In the book I am currently working on, Junkin looms large, as much of it takes place in Lexington, Virginia at both Washington College and at the nearby Virginia Military Institute, where the Davidson family had strong ties. In Junkin we get a glimpse of so much of the Mainline of the mid-nineteenth century, one that was dominated by the evangelical Protestant denominations of the Second Great Awakening (the Methodists, the Baptists, and the Presbyterians). But we also get a glimpse at how fragmented that evangelicalism was. All three of those denominations, the largest churches in the United States, split over the issue of slavery in the years before the Civil War. In the case of the Presbyterians, they had already broken into two camps over other issues (though slavery played an increasing role), but had managed to largely stick together somewhat officially until nearly the very end.

When it came to slavery, Junkin and the Old School walked a very fine line. Junkin himself owned slaves (after he moved to Virginia to take the Washington College job), had attacked abolitionists (while living in Ohio), but also supported the American Colonization Society. Indeed, he probably got the job in Lexington, in part because the previous college president had become to vocal on his belief that slavery had led to economic stagnation in Virginia. His branch of the Presbyterian denomination found no Biblical reason to believe slavery to be a sin, though most Northern Old Schoolers did believe it (like virtually any human institution) could lead to sin. By the time of the Civil War, however the Southern component of the Old School was less and less likely to agree with their Northern counterparts, and indeed, would form their own denomination as war clouds began to gather.

What does this have to do with the Mainline of today? Well, several things actually. First, is that theological and doctrinal complexity (and sometimes gymnastics) are nothing new within the Mainline. While we might talk of the "evangelical denominations" (and I surely do), there were very real difference between and among the Methodists, Baptists, and Presbyterians of Junkin's time. They did not always agree with each other, internally or externally, and it would be surprising if the modern Mainline did as well. Likewise, those differences mattered, and in someways drove membership and engagement that makes modern "consensus" efforts look meager in comparison. They may not have always been right, but they also weren't always wrong on matters of faith either. Second, is that these denominations were fully engaged with both their nation and their national culture. They were active in trying to shape it (whether in condemning slavery as a sin, working to keep the nation together, or -- even-- in trying to form a new nation in the Confederacy), much more than they were being shaped by it. And they were calling their members to political action (in ways that would probably make modern Church/State separationists's heads spin). Recent scholarship (such as the this) that in essence blames the rise of evangelicals and their engagement in politics on the slavery issue as the chief cause of the Civil War -- or else the inability for politicians to craft a compromise short of war misses the point that denominations were already engaged on both sides of the issue (and that evangelicals in England had helped end slavery there without a war). Junkin's story also reminds us of one other thing, using political labels like "liberal" and "conservative" can be problematic. Some recent scholarship (see here for an example) has argued that liberal Protestantism of the mid-nineteenth century gave birth to the liberal Protestantism of the early twentieth (and hence, to that of the twenty-first century as well), in large part because they had to reject Biblical literalism in order to condemn slavery. But Northern Old School Presbyterians never doubted that slavery could lead to sin, even if it was mentioned in the Bible. What they wrestled with was how to deal with the institution. In short, there is much more complexity to their time, and to ours, than labels often have us believe. And Junkin proved, as much as he was a man of his time, to be able to be "liberal" on some things, and "conservative" on others. Indeed, it was his conservatism that made him into a Unionist--to the point that he shook the very soil of Virginia off his shoes and wiped it from his wagon wheels when he left the state.

As for Junkin and Gettysburg, after leaving Lexington in the spring of 1861, Junkin returned to Pennsylvania. After the battle was over in 1863, the aged reverend made his way to Gettysburg, where he began ministering to the wounded and amongst the captured Confederates as well. Among the prisoners, he discovered several former students, whom he astounded by pulling from one of his pockets a class list and talking about their course work and grades. Surely this was a surreal moment. Surely as well it was a reminder of what they (and the nation) had once been, and would one day be again.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)